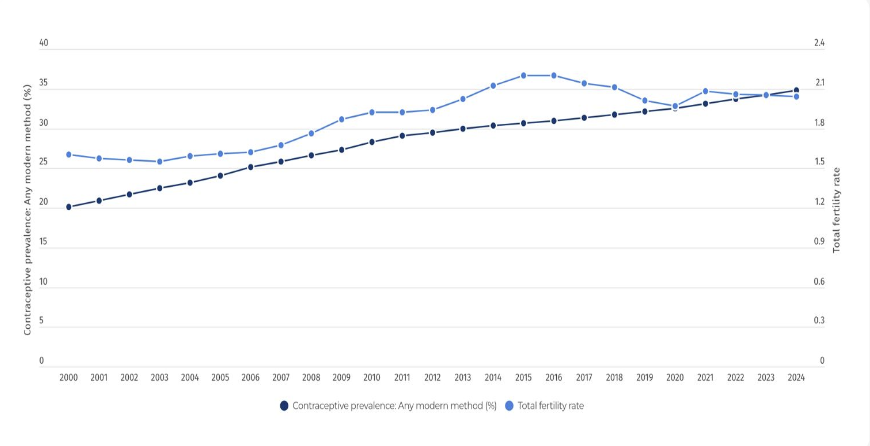

Decreasing fertility rates is a global trend that we can observe in an ever-larger number of countries around the world. More than two-thirds of the world population already live in countries with fertility rates below replacement level. This trend has been accompanied by one of the most successful transformations in human history: the process of liberating women from traditional gender roles, discrimination and violence, and expanding access to education and the workforce. All over the world, women are increasingly empowered to make decisions about their bodies and lives. This is a basic human right, and the fact that more and more women can make these choices freely is one of the greatest achievements in human development. The broader impact is huge: fewer women die giving birth, more newborns survive, smaller families mean more investments in a smaller number of children with better educational outcomes, more women can complete their education and enter the workforce – the list goes on and on. UNFPA’s work, together with partners, to ensure women have access to family planning information, services and supplies has been a crucial enabler of this success.

Societies have benefited tremendously from the increasing inclusion of women in public life and the economy, and the accompanying shifts in social norms. Women are not valued any longer primarily for their role in reproduction, but as equal members of society with equal rights and dignity. This has also meant that social pressure and expectations on women to have children have diminished. And with greater legal equality and economic independence, women increasingly can make their own choices about whether and when to have children, and how many.

The choices people make around having children are influenced by a complex mix of personal, social and economic factors. Generally, in high-income countries, people would like to have more children than they end up having. Governments have tried to influence people’s fertility choices and get women to have more children. Some have offered financial incentives such as baby bonuses or tax breaks. Others have even moved to limit women’s reproductive rights, for example, by making it harder to access abortion and contraceptives. None of these measures have led to lasting significant increases in fertility rates. Even in countries with generous institutionalized support for families, such as France and the Nordic countries, fertility rates have remained below replacement level and have recently declined.

Even if it were possible to easily boost fertility rates, the effects would only be felt many years later and, if other challenges remain unaddressed, might just add to emigration pressure – and to young people taking public investment in their education with them when they leave.