Armenia is working to ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Today, almost 100 per cent of births in Armenia take place in maternity hospitals, but more needs to be done to dismantle stigma and other barriers preventing the most vulnerable from accessing services.

“Have you come to be sterilized?” the doctor asked Karine Grigoryan, 40 years old, from Armenia. “No,” she said. “The opposite.”

Ms. Grigoryan had recently got married and wanted to start a family.

“I dreamt of having a child and I realized that I didn’t have much time,” she said. “I decided not to wait. I visited a provider of reproductive and family planning services to start in-vitro fertilization.”

That’s when the doctor asked about sterilization.

"Many doctors don't know that not all disabilities are passed on genetically," she said. "I knew my disability would not be passed on to my child, and I knew that nobody can tell me whether I should or should not have a child."

Ms. Grigoryan acquired a mental disability at birth as a result of her mother’s difficult labour.

“I wondered how many women with disabilities - who are not well-informed - back down on their decision to have a child because of such doctors,” Ms. Grigoryan said. “No-one can tell us whether we should or should not have a child.”

While Ms. Grigoryan faced stigma when she wanted to be a mother and overcame barriers to do so, Armenia has, overall, made great progress on maternal care. Nearly 100 per cent of births are attended by a reproductive health professional and inequalities of access have been greatly reduced.

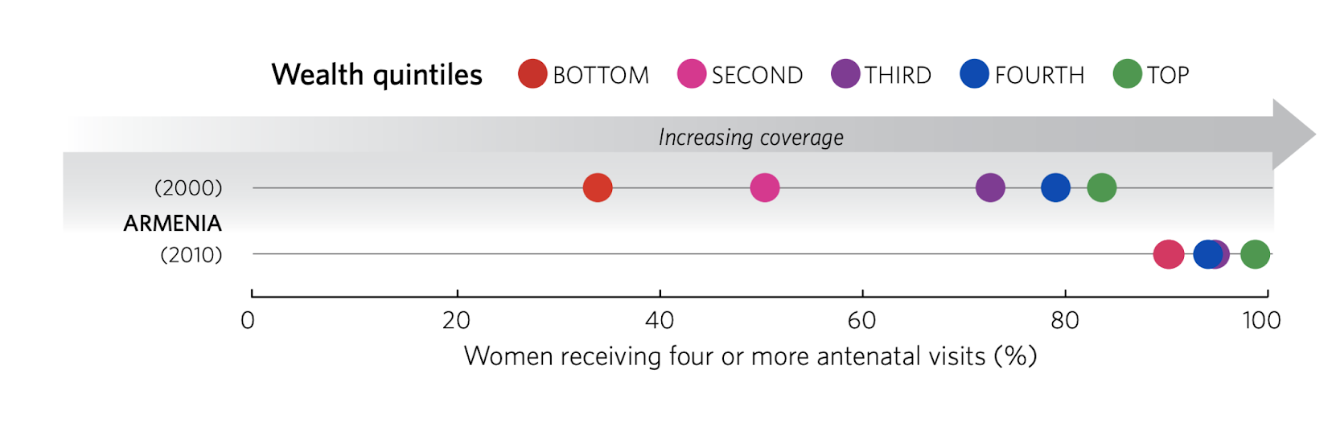

In 2000, only 83 per cent of births were assisted by a health professional. Then, in 2008, Armenia almost doubled budget allocations for maternity care and introduced certificates entitling pregnant women to free services. As a result, women in all wealth quintiles had better access to services than they had before, and previous inequalities were largely erased.

Today, according to data from the Government of Armenia, only 0.033 per cent of births occur outside of maternity hospitals. In addition, prenatal and postnatal care, including prenatal screenings, are free of charge in Armenia, contributing to early diagnosis of any complications during pregnancy, followed by timely treatment when needed and a decrease in maternal mortality.

In 2019, at the Nairobi Summit, Armenia committed to further expanding access to reproductive health and family planning services and information, and UNFPA has provided support in ensuring that all women and girls, irrespective of their status, have access to the services they need.

Despite the initial difficulty convincing her doctor, Ms. Grigoryan was perfectly able to have a child and received the support she needed during her pregnancy and when she gave birth.

“Everyone was saying that, at a mature age and with a disability, having a child will be a risk for life,” Ms. Grigoryan said. “But I had a perfect pregnancy. Every month I would go and have my regular check-up and many people I knew were surprised that I was going through pregnancy so lightly. Seeing me at the hospital being so positive and optimistic, and also seeing that my child did not have any disability, also surprised them very much.”

Ms. Grigoryan was already a campaigner for people living with disabilities. Inspired by a course she attended in Oregon in 2007, she became a civil society activist and founded Agate, a non-governmental organization with a mission to unite women with disabilities in Armenia.

She was surprised how becoming a mother herself empowered other women living with disabilities.

“In the past, I tried to empower women with disabilities by saying: you have a right to love and to be loved, you have a right to become mothers,” she said. “But, the example I set in my own life proved to be much stronger than my words.”

“Access to quality maternal health services for all is at the heart of UNFPA’s work,” said Tsovinar Harutyunyan, head of the UNFPA Office in Armenia. “Working together with the Government of Armenia, and our partners, we are delighted to see such a vast improvement in reducing inequalities in access to maternal health care and sexual and reproductive health services.”

Despite this progress, more needs to be done to eradicate the remaining inequalities in access to maternal health care, including for people with disabilities. For her part, Ms. Grigoryan continues to campaign to empower women living with disabilities so that they can overcome stigma and stereotypes and start families of their own.

“I have spoken to many healthcare providers at reproductive health centres and changed their opinion about women with disabilities,” Ms. Grigoryan said. “Stereotypes against people with disabilities put us in a box as if for our whole life we have to prove that we are able.”