ISTANBUL — Millions of women and girls in Eastern Europe and Central Asia lack the power and agency to make choices about their own bodies, without fear of violence or having someone else decide for them. This dangerous lack of bodily autonomy has deep-seated, but often under-recognized roots.

“From a very young age, kids are constantly getting the message that I don’t have control over my body and what happens to it,” said Anja Rubik, a model and activist from Poland who works to promote comprehensive sexuality education. “They’re taught that I have to do what I’m told, to go sit on someone’s lap or give them a kiss, even if I don’t want to, or other people will be upset.”

These kinds of attitudes can set the tone for unhealthy adult relationships, in addition to leaving children vulnerable to abuse.

“I felt a kind of guilt about having been silenced as a child, like if I had said something to my parents then, maybe other girls in my family wouldn’t have experienced the same thing,” said Olga Lucovnicova, a Moldovan director who made an award-winning short film about confronting the uncle who sexually abused her when she was young.

Rubik and Lucovnicova both spoke about their experiences as part of the regional launch of the UNFPA State of World Population Report 2021, “My Body is My Own,” on claiming the right to bodily autonomy and self-determination. Hosted by Turkish journalist and news anchor Afşin Yurdakul, the 14 April online event addressed the many ways in which bodily autonomy and bodily integrity are threatened, and the consequences for women, girls and society as a whole.

“Bodily autonomy is a foundation for the enjoyment of all human rights, including the right to health and the right to live free from violence,” said Alanna Armitage, UNFPA Regional Director for Eastern Europe and Central Asia. She shared the tragic story of Aizada Kanatbekova, a 27-year-old woman in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, who was abducted and strangled to death on 5 April, reportedly by a man whose advances she had rejected.

“This horrible murder is an example of the most extreme form of violation of bodily autonomy and bodily integrity,” Armitage said.

Though women and girls in Eastern Europe and Central Asia generally have more bodily autonomy than the global average, their rights are still violated on a regular basis through harmful practices like virginity tests, “honour” killings, child marriage and bride kidnapping. In Kyrgyzstan, for example, one in five marriages involved an abduction.

And the share of women in the region not fully empowered to make choices over health care, contraception and the ability to say yes or no to sex is still significant: 19 per cent in Ukraine, 23 per cent in Kyrgyzstan, 31 per cent in Albania and 34 per cent in Armenia. In Tajikistan, 67 per cent of women cannot make autonomous decisions on these fundamental issues.

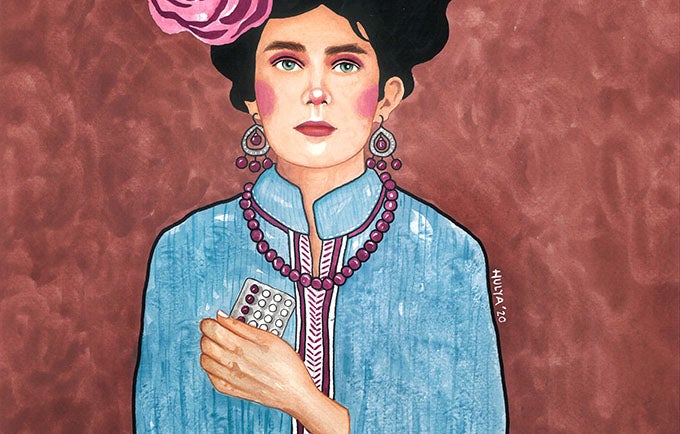

“Women’s sexual and reproductive health is key to a healthy society, but so many people close their eyes on this topic because of the taboos and stigma around it, which contribute greatly to gender inequality,” said Natalia Vodianova, a UNFPA Goodwill Ambassador from Russia who advocates for reproductive rights, comprehensive sexuality education and ending the shame around menstruation.

Though deeply harmful, these kinds of taboos and stigma are not inevitable.

“People build customs and tradition, so people can change customs and tradition, and the only way to do that is through education,” said Rubik.

Silvia Sinani is working to do just that as a performer in the Roma girl band “Pretty Loud,” whose music blends rap and hip-hop with traditional rhythms from her Roma community in Serbia. Child marriage is particularly prevalent among Roma in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, and Pretty Loud’s songs convey strong messages about girls’ empowerment.

“Music is a way we can talk about the problems in our community, about the relationship between parents and their daughters, about poverty, dropping out of school and the expectation that girls must be virgins until marriage,” Sinani said.

“Change will not come by itself. We are agents of change,” agreed Vitaly Djuma, the executive director of the Eurasian Coalition on Health, Rights, Gender and Sexual Diversity.

Though being LGBTQ is not outlawed in most countries in the Eastern Europe and Central Asia region, stigma, discrimination and legal barriers limit basic freedoms such as having a family or walking down the street safely, Djuma said.

“Denial of bodily autonomy is robbing us in the LGBTQ community of our dignity, of our health, our happiness,” he said. “We are constantly being told we are second-class citizens. Transgender people in much of the world have no say even in determining what gender they belong to.”

“Being in control of your body means being in control of your life,” moderator Yurdakul emphasized.

Persons with disabilities are also particularly vulnerable to violations of their bodily autonomy. Girls and boys with disabilities are nearly three times more likely to be subjected to sexual violence, with girls at the greatest risk, Vodianova pointed out during the panel. And adults with disabilities are often denied the right to their own reproductive choices, she added. “It’s often believed that women with disabilities should not have children, and contraception is sometimes even forced onto them,” Vodianova said.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated global threats to bodily autonomy by increasing sexual violence, creating new barriers to health care, and driving job and education losses, which have been experienced at a higher rate among women.

Dismantling pervasive social norms of gender inequality is essential to ensuring bodily autonomy for all, Armitage said.

“We are talking about things that many people don’t want to talk about. They are painful and they can be life-threatening and life-changing,” she said. “But we do not have to accept the status quo.”