TÂRGU MUREȘ, Romania – When millions of Ukrainians fled their homes at the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion in early 2022, many said they thought it would only be for a couple of weeks until things settled down and allowed them to return.

But as the violence has continued and escalated, now in its third year, the reality of being a Ukrainian refugee has changed. Some have gone back despite the dangers, still drawn to the feeling of being in their homeland. Millions of others have remained abroad, scattered in countries with different languages, cultures and ways of life – forced to adapt and make it their own.

Starting from scratch comes with a range of struggles: from simply finding friends and community, to more complicated tasks like navigating an unfamiliar bureaucratic system and accessing health care, emergency protection and support services, education, and jobs – all in a different language and culture. On top of that, women with young children must also find childcare options that allow them to job hunt or go to work and juggle all their responsibilities outside of the home.

In Romania, an estimated five million Ukrainian refugees have crossed the border since the invasion began, with more than 160,000 recorded in the country as of July 2024, according to UNHCR. In order to help respond to their needs, UNFPA worked with its longtime partner, the East European Institute for Reproductive Health (EEIRH) and the Government of Romania, to open four Women and Girls Safe Spaces across the country in 2022.

In Romania, an estimated five million Ukrainian refugees have crossed the border since the invasion began, with more than 160,000 recorded in the country as of July 2024, according to UNHCR. In order to help respond to their needs, UNFPA worked with its longtime partner, the East European Institute for Reproductive Health (EEIRH) and the Government of Romania, to open four Women and Girls Safe Spaces across the country in 2022.

They aimed to reach out to women and girls in the Ukrainian refugee community – some who were forced to leave their country, by themselves, for the very first time – and provide them with a support network to lean on. The Safe Spaces also empowered these refugees to draw on their knowledge and skills to participate in their community’s recovery and rebuilding.

“It was like being thrown a lifesaver,” explained Hanna Lukianchenko, a Ukrainian refugee who joined the Safe Spaces team in the northern Romanian city of Târgu Mureș. Even after the Safe Spaces project was completed at the end of 2023, Ms. Lukianchenko said its impact continues to be reflected in the girls and women who were able to learn, adapt and thrive through its services: “The Safe Spaces really became an island of independence. They were a place where Ukrainian women could feel themselves again, be independent and say what they really think.”

A Safe Space to rebuild community and connection

Before Russia launched its full-scale invasion, Ms. Lukianchenko, 39, was a litigation lawyer in the southern Ukrainian city of Odesa known for handling complex cases that even reached the Supreme Court. In the first days after Russia’s attacks, she fled with her husband and daughter to the northern Romanian city of Târgu Mureș. There, she continued to draw on her lawyerly nature to speak out and advocate on behalf of the growing Ukrainian refugee community forming in the region. She soon became known as someone who could bring people together and get things done.

That caught the attention of the local Safe Space, which recruited Ms. Lukianchenko as a facilitator. Together they began organizing group activities, like holiday parties, concerts and family camping trips, as a way to rebuild the sense of community and connection that had been lost in the war. “Many Ukrainian families had to move between regions or to other countries many times or even went home because they couldn't integrate,” she said. “But here, we had so many activities and we started to speak more with each other, and that made people think, ‘This is interesting, I can stay here longer.’”

A Safe Space to access health care and information – sometimes for the first time

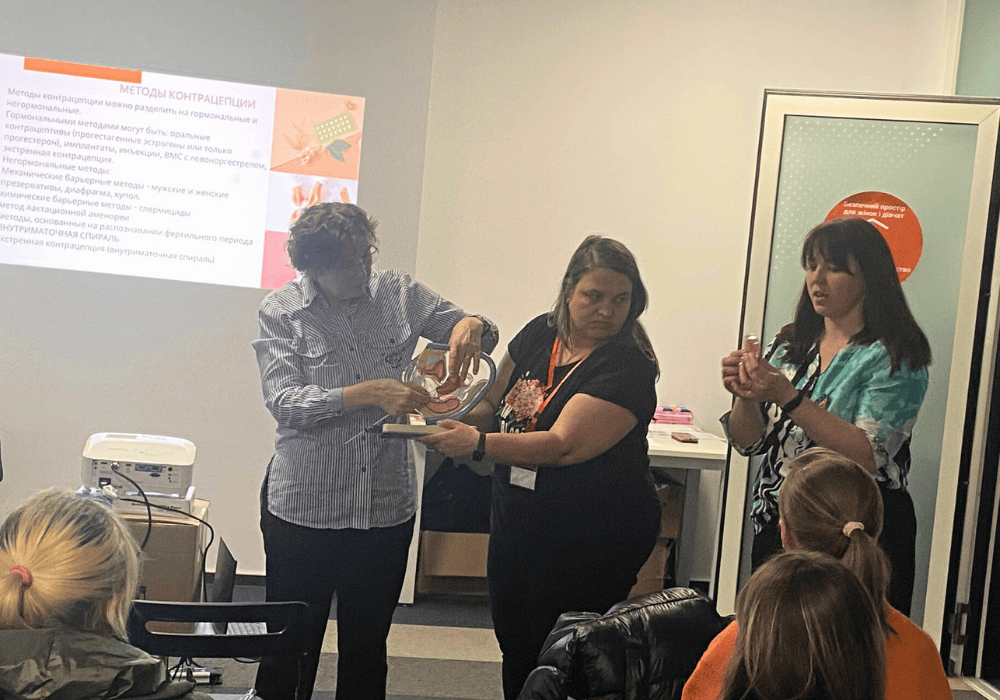

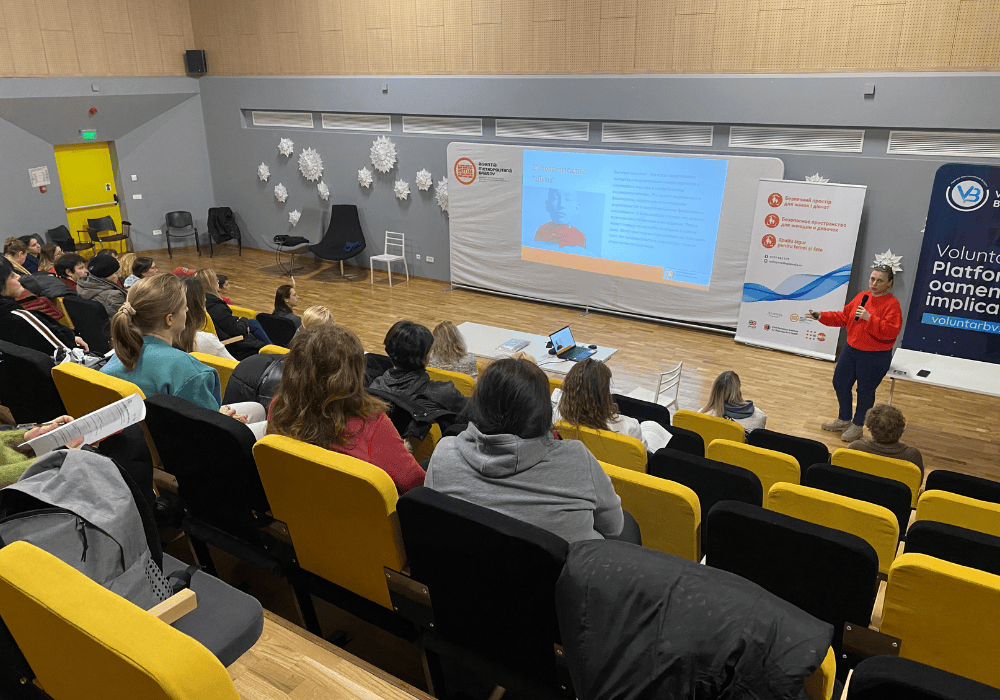

Another key function of the Safe Spaces was to be a source of information for Ukrainian refugees living in a country with a different language and way of doing things. Each Safe Space hosted sessions featuring experts from various fields, including doctors, psychologists and police officers, to discuss issues relating to women’s health, rights and services. For Ukrainian women and girls, it offered a rare opportunity to ask questions in a private and supportive environment and to receive answers translated back to them in their own language.

“It was such interesting, useful information we had there, that we never heard before even when we were in Ukraine,” Ms. Lukianchenko recalled.She said these sessions usually led to women returning to the Safe Space with follow-up questions about other health procedures such as HPV vaccinations, pap smears and menopause care. She would then organize visits to clinics, where patients would be accompanied by a health mediator to help guide them through the medical system and find the right service provider.

“In Târgu Mureș, there are no Ukrainian women who have not gone to the gynaecologist this year,” Ms. Lukianchenko said proudly, describing her work that not only covered treatment for women with complaints, but also prevention to make sure women do not get sick. “And they feel less stressed when they go to the doctor with us. It’s a secure feeling because they can tell what they need and understand what the doctor is telling them back. This is very important.”

About 200 km south, at the UNFPA Safe Space in the city of Brașov, Natalia Vataman helped spearhead a similar programme. The 40-year-old first arrived from Ukraine years earlier with her husband and two young daughters in 2015 when Russia first began making advances in the eastern regions. At that time, there were relatively few refugees crossing the border into Romania and systems still needed to be set up to support them. Ms. Vataman was forced to overcome the language and cultural barriers on her own – but that made her determined to become the support system for others that she never had. “I left Ukraine, but Ukraine did not leave my heart,” she said. “And I had made a plan for every problem I faced: the bank, the hospital, the school, the government. I wrote down everything, so I was ready when others came.”

Each Safe Space tailored its activities to meet the needs and interests of its community. Those living in Brașov had a higher proportion of women of reproductive age, increasing the demand for maternal and sexual health. So Ms. Vataman developed a system to help people access and navigate these services through the UNFPA Safe Space.

The lobby of the Brașov Safe Space was transformed into a health care coordination, triage and treatment centre, with reception tables for women to register and group trips organized every day for medical consultations. Each patient was assigned a translator who was trained to communicate their health needs while ensuring their privacy. At the doctor’s office, the patient would receive immediate care, medical prescriptions or be referred for specialist treatment. For Ukrainians, this offered a streamlined system that took into account their language and cultural sensitivities. At the same time, it helped to ease the pressure on Romania’s public hospitals, which were not equipped at the beginning of the refugee crisis to handle such a rapid influx of Ukrainian patients.

Ms. Vataman teared up thinking about all the women who had been helped through the UNFPA Safe Space: a woman who survived ovarian cancer because she was taken to a gynaecologist who detected the tumour at a stage when it was still treatable; another who avoided a costly and unnecessary procedure after getting an appointment with a specialist gynaecologist; and many others whose outlook on life improved because they understood their female bodies better and had easier access to sexual reproductive health care.

A Safe Space to speak out and be heard

Anastasia Krylova, 42, attended some of the information sessions at the Safe Space in Brașov. She was interested in the sexual and reproductive health topics she heard, but saw a need to address mental health as well.

Ms. Krylova had been a psychologist with her own private practice back in Mykolaiv, a city in southern Ukraine that became a front line of the fighting. She had specialized in treating survivors of abuse and trauma and believed that similar counselling services would help those escaping the war.

When she proposed holding a group mental health support session for Ukrainian refugee women, she was met with scepticism. Due to Ukrainian culture, some members of the Safe Space were unsure whether people would be willing to open up and share their emotions in front of a group of strangers.

But Ms. Krylova persisted with her idea, and when she held her first Safe Space talk, more than 150 women attended. She continued to hold weekly meetings that focused on different issues: “The first half, I would just speak and explain some theories, about avoiding manipulation and intimidation, for example. And after that, we would start talking. They would ask something, we would discuss and I would answer. Sometimes we would do some exercises.”

And as women kept coming back for the group sessions, Ms. Krylova began offering one-on-one counselling. She said many of her initial cases were related to the stress and frustration of being displaced by conflict and the strain caused on family relationships: “Because of the war and restarting their lives and not finding good jobs like they used to have in Ukraine, the parents have a lot of anger inside and they can give that anger to their teenagers and their little children.”

However, soon she began hearing more stories of women experiencing gender-based violence, especially intimate partner violence. Women would ask her how to deal with jealousy from boyfriends who were still in Ukraine or husbands who were becoming more controlling. “Because when they come, men start working and women stay with the children, and so there is just one person with money, mostly the man, and there start to be problems with how he uses his power,” Ms. Krylova explained. “Women can't go out or say no to anything.”

One case that stood out in Ms. Krylova’s mind was of a young woman who started in her group therapy classes. “I was surprised that she was younger than me because she looked very tired when I met her,” Ms. Krylova remembered.

The woman told Ms. Krylova how her husband was violent toward her and constantly pressured her to have a baby. She wanted to leave him but felt trapped without any work or means of her own. Ms. Krylova met with her for group and one-on-one psychological support sessions and, through the Safe Space, connected her with services in other sectors, including legal counselling and medical referrals as well as language and job training.

In July, Ms. Krylova got a video call from the woman. “I was in shock,” she said. “ She was so beautiful, and I was like, wow, what happened? And she said, ‘I found a job, I left him and I’m free.’”

Ms. Krylova, like most of her former colleagues at the Women and Girls Safe Spaces across Romania, keeps in touch with people she met and still tries to help those in need when she can. She thinks of the Safe Spaces fondly and holds out hope that a similar project will one day return. “Having the Safe Space gave Ukrainian women the power to restart and to live again,” she said. “We helped a lot of women – and I know there are more we can help.”

--

The Women and Girls Safe Spaces project in Romania was completed with funding from the US Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office.