BRAȘOV, Romania – “In every activity I do, extra effort is needed because I run into all kinds of barriers,” said Raluca Cozmuța. “I considered the extra effort normal because that is what I and other people with disabilities were taught.”

Ms. Cozmuța, 37, has a limb deficiency in her left arm. She also has four brothers with medium to severe degrees of intellectual disabilities. They have struggled their whole lives not only to get the support they need, but also to be respected by others: “Over time it is quite difficult and frustrating that the world only sees your disability and you rarely get chances to show that you are actually more than that – you are human, you are normal and you can do things.”

These personal experiences made Ms. Cozmuța even more eager to join a UNFPA pilot project for survivors of gender-based violence (GBV) in Romania, including Ukrainian refugees. Its aim is to make services more accessible for people with disabilities. Six organizations – four non-governmental organizations and two state providers – were chosen to participate. Ms. Cozmuța represented the government of Șomcuta Mare, a city located just 100 km from Romania’s northern border with Ukraine. She has worked in the city’s social assistance department for more than 15 years, helping those with disabilities access benefits like aid reimbursements and special permits. But she said the pilot project was the first time she had thought about inclusion in terms of GBV responses.

Globally, 16 per cent of the female population has a disability, and they are up to four times more likely to experience intimate partner violence than those without disabilities. Inclusive services are especially critical in emergency situations, like the war in Ukraine, where refugees are torn away from their usual safety and support networks. UNFPA is committed to the principles of leaving no one behind and reaching the furthest behind to ensure vulnerable and marginalized groups can participate in and benefit from all development progress.

However, in Romania, understanding what accessibility entails remains a work in progress. “As a society, we are not inclusive,” said Laura Istrate, from the Agapedia Foundation, one of the NGOs participating in the pilot project. “The government has signed many international agreements on disability inclusion, but we are still more reactive, not proactive.”

She pointed out that accessibility is usually only thought of in terms of building infrastructure, such as wheelchair ramps or automated doors. These types of changes require significant investment that few local NGOs can easily afford. They also take a narrow view of inclusion that only improves conditions for people with physical mobility difficulties, while still failing to address the barriers that exist for those who are deaf, blind or have mental, intellectual and psychosocial disabilities. Ms. Istrate emphasized that raising awareness was a crucial first step. Even small, initial actions could help organizations understand the full scope of existing needs.

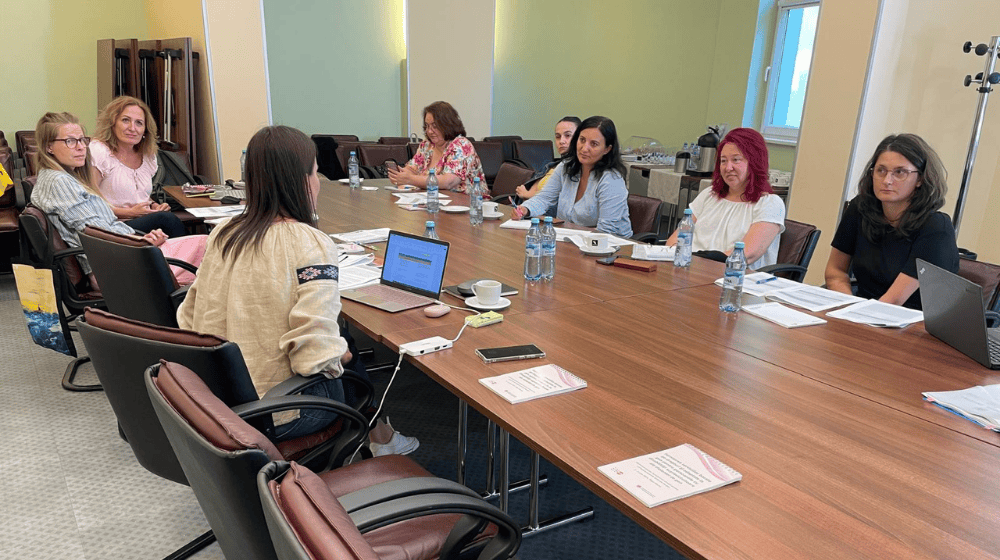

As part of improving this awareness, the six pilot organizations conducted an assessment of their current accessibility levels using a tool developed by UNFPA. After completing the assessment, each organization created an action plan – and changes are already being seen.

One of the state providers realized it did not have any questions in its intake forms to indicate whether a GBV survivor had disabilities. Within two weeks of starting the pilot project, they added a section asking if a survivor has any disabilities and what kinds. Collecting this data will allow the state provider to understand for the first time the accessibility needs of its patients and adapt its procedures to better serve them in the future.

The Agapedia Foundation is making changes that seem simple but could have a big impact, too. Its action plan details how online and social media content should feature alternative text and captions. This could significantly expand its reach among people who were previously excluded due to vision or hearing impairments and create new avenues to deliver services to them. “We still don’t have a wheelchair ramp, but there is nothing that says we have to meet at our office. We can go to them. The important thing is that people with any kind of disability know what we offer and how to contact us if they need our help,” explained Ms. Istrate. “I never thought of this before.”

The East European Institute for Reproductive Health (EEIRH), UNFPA’s partner in Romania overseeing the pilot project, is also reaching out to more organizations of persons with disabilities. EEIRH’s programme coordinator and GBV specialist Ionela Horga explained that it is important not to see all disabilities as a homogenous group that shares the same needs and suffers the same disadvantages. “A person who has a physical disability does not necessarily know what someone who is blind or deaf goes through. We need to meet each group on their own ground,” she said. EEIRH is planning follow-up accessibility audits and training sessions with diverse groups so that inclusive policies and practices can continue to expand and improve.

Ms. Istrate from the Agapedia Foundation added that the UNFPA project is already building momentum to shift mindsets: "It has gotten the conversation about disability inclusion started. Even that was missing before in Romania."

And that has given Ms. Cozmuța hope that in the future people with disabilities will not have to face the same challenges as her and her family. “Through this project, I met concerned and passionate people, which made me more optimistic and believe that programmes and activities will be developed that will really benefit people with disabilities,” she said.

–

This project was completed with funding from the US Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration and the Government of Sweden.