ABSHERON, Azerbaijan – Fourteen-year-old Maryam stood, awe-struck, at the edge of an indoor football pitch in Absheron, Azerbaijan. “For me, seeing a real soccer pitch, a real goal net, and putting on a real soccer jersey has been utterly shocking,” she said.

Life is often isolating for young people like Maryam, who is living with Autism. In Azerbaijan, nearly half of youth with disabilities are educated at home, away from their peers, according to a 2010 survey.

And girls living with disabilities often have fewer opportunities to engage with the broader world than boys. In the first year of a national pilot project to promote inclusive education, only five of 20 participants were girls.

In April, UNFPA began working with the Special Olympics to create opportunities for adolescent girls to play and learn. The project will provide sports activities for both girls with disabilities and those without. The participants will also learn about their reproductive health and their human rights.

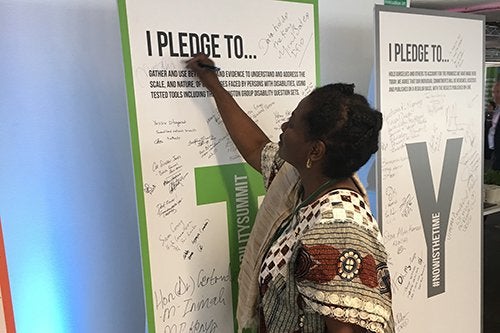

At the Global Disability Summit in London, UNFPA Executive Director Dr. Natalia Kanem signs a pledge to promote data gathering on the needs of persons living with disabilities. UNFPA is conducting a global study on the sexual and reproductive rights of young people with disabilities. © UNFPA/Matthew Jackson

The first training session was held recently at a sports stadium outside Baku. Dozens of girls in football jerseys practiced passing the ball to one another.

“I always wanted to play with my peers, but nobody treated me as an equal,” said Aishe, 15, after dribbling the ball down the length of the court. “Now, here we play with girls who know our struggles but don’t perceive them as an obstacle to playing as team.”

Stigma and discrimination

The partnership aims to help some 40 participants, aged 14 to 17, reap the benefits of team sports: They will gain confidence and physical fitness, learn to collaborate, and develop a sense of achievement and empowerment.

These qualities are especially important for girls living with disabilities, who are extremely vulnerable but are rarely taught to stand up for themselves.

Women and girls in Azerbaijan, in general, face an alarming risk of violence. A 2008 study by UNFPA found that, among survey participants, 10 per cent of women had experienced sexual abuse before reaching age 15.

These risks are even greater among disabled persons. Studies from around the world show that people living with disabilities are significantly more likely than non-disabled persons to experience physical or sexual violence. Children with intellectual disabilities are among the most vulnerable, facing as much as 4.6 times the risk of sexual violence.

Yet young people with disabilities are less likely than their peers to receive information about their bodies and rights.

“They face extreme stigma and discrimination – laced with assumptions that they do not need sexual and reproductive health services because they are asexual,” UNFPA Executive Director Dr. Natalia Kanem said today at the Global Disability Summit in London.

The programme in Azerbaijan is designed to help girls develop confidence, and to help them learn about their reproductive health. © UNFPA Azerbaijan

“They are denied access to comprehensive sexuality education, limiting their ability to have safe, healthy and enjoyable relationships. Decisions about their bodies are taken for them,” she said.

Opening a door to the world

Comprehensive sexuality education teaches young people about their sexual and reproductive health, human rights, and how to engage in mutually respectful relationships.

The youth football programme in Azerbaijan aims to deliver exactly this kind of information to its participants.

The girls will learn about their bodies and reproductive health, with lessons covering topics such as sexually transmitted infections and family planning. They will also receive information about how they can seek health services. And they will learn to identify forms of gender-based violence and how report violence if they witness or experience it.

But the social aspects of the programme are no less important.

The friendships and camaraderie they develop can help open a door to the wider world.

“It was great to see the girls play together,” Jenni Hakkinen, Special Olympics regional manager for youth, schools and universities, told UNFPA at the end of the first training day.

“There was a lot of energy and talent on the field,” she added. “I could see friendships beginning to blossom among the players.”

—Farhad Hajiyev