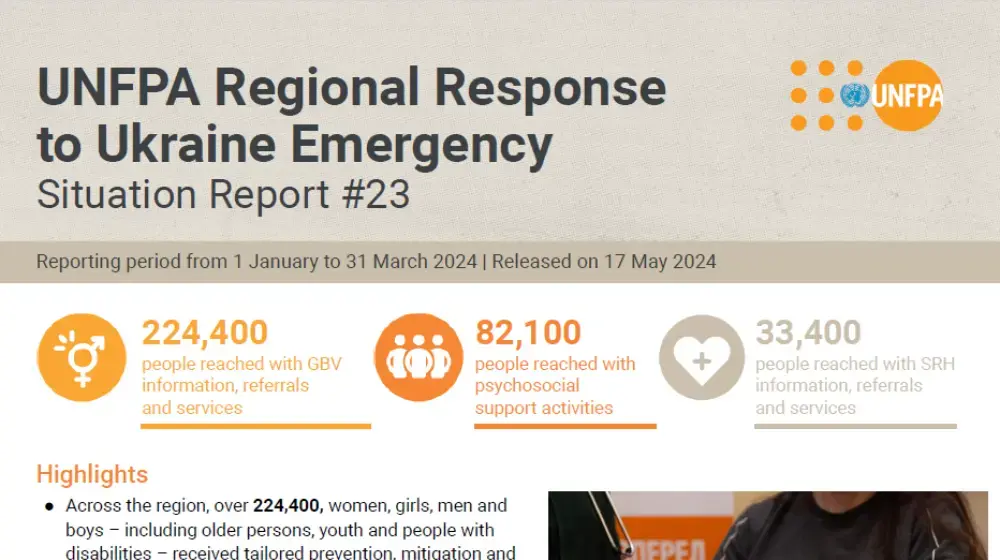

LOZOVA, Ukraine – “I don’t remember the first time my husband beat me,” says Iryna, age 33. “Only the pain, shame and tears.”

But she remembers the last time.

As the now two-year-old conflict in eastern Ukraine raged on, the already struggling economy in Iryna’s small village in Lozova district, less than 200 kilometres outside the contact line, had been steadily declining. Her husband was unemployed and drinking heavily, and, unable to pay many of their bills, they no longer had gas or electricity.

Amidst the strain, their home had become a tinderbox of tension, and her husband’s abuse was growing more frequent. However, Iryna did not know of any social services or resources for victims of gender-based violence (GBV) near her isolated village, so she suffered in silence, ashamed, and even blaming herself for causing the abuse by not being a good enough wife.

Then one day, her husband began to attack her, a now common occurrence, but this time, their 7-year-old son stepped between them to try and protect his mother. Her husband then beat him instead, as his two younger brothers, ages 5 and 6, looked on.

And with that, Iryna had had enough. She called the police, and they soon arrived along with a UNFPA mobile team that offers GBV services in hard-to-reach places impacted by Ukraine’s conflict.

Though domestic abuse calls often do not result in arrest, with the mobile team on hand to guide the process, Iryna’s husband was taken into custody and eventually convicted for his crime. And the team members immediately set about providing Iryna and her sons with counselling and referrals to other critical services.

Svitlana is one of the over 4,000 women helped by the mobile clinics between November and April. © UNFPA Ukraine/Maks Levin

Rates of gender-based violence spike amidst conflict

Globally, rates of GBV greatly increase during conflicts and other humanitarian crises. In Ukraine, a nationwide survey conducted by UNFPA in 2014 showed that 22 per cent of all women of reproductive age had suffered sexual and physical GBV at least once.

And in the conflict-afflicted regions, including Kharkiv region where Iryna lives, a 2015 UNFPA survey showed that women most-impacted by the conflict, those now internally displaced, are three times more likely to have suffered GBV during the conflict period than other women.

In response to the rising rates of abuse, in November UNFPA began dispatching 21 mobile teams, each consisting of two psychologists and one social worker, to remote towns and villages in the five most-impacted regions.

“The difficult economic situation, which is badly exacerbated by the ongoing fighting and limited culture of dialogue [in Ukraine], leads to frequent conflict situations in families,” says Dmytro Bylkiv, the leader of one of the mobile teams. “Our work is focused on preventing violent situations and on finding solutions. The most important thing is to give hope and to convince people that all conflicts are solvable [without violence], while also giving out information on public organizations and services that can help.”

In addition, the teams also perform outreach to law enforcement and other local authorities, including the media, to help improve their awareness of and response to GBV. And they have distributed tens of thousands of cards and posters with information about their services and how to contact them in popular local spots, like the post office, where women might find them.

And more and more women are reaching out.

Bringing critical care to isolated women's front door

Svitlana, a single mother of three, is among the over 4,000 women the teams supported in the privacy of their own home between November and April. And while their main focus is GBV, they also provide psychosocial support to women, many traumatized by the conflict, who have never before had the opportunity to receive such services in their remote areas.

Women displaced by the conflict, like those receiving supplies above, are three times as likely to have suffered GBV during the conflict period as other women. © UNFPA Ukraine

After the conflict forced her to move from her home to the remote village of Zorya, Svitlana was isolated from family and friends. Feeling alone and trapped, she fell into a depression.

“Every day I struggle for a better life for my children,” she says. “Sometimes I lie in bed and cry for hours while they are sleeping.”

After spotting a card with the number to contact a mobile team, Svitlana reached out. The team arrived at her door, offered counselling and gave her information about other social and psychological services she is eligible for that she had not previously known existed.

Then they told her not to hesitate to call them again if she needed support, and they would promptly come knock on her front door.