"I only discovered I was HIV positive when I became pregnant,” said Aynishan Hasanova*, 27, from Lankaran, a city in southern Azerbaijan. “My husband was infected a long time ago, but he concealed it from me. I thought my child would also be infected."

According to the latest official figures, 919 people in Azerbaijan were infected with HIV in 2023, and around 7 per cent of them were pregnant women. But there are now treatments and procedures that limit the likelihood of the virus being transmitted to the child.

In November 2023, Ms. Hasanova visited the Lankaran Regional Perinatal Centre to give birth. “The doctor told me the child could be protected from HIV if I had a caesarean delivery, didn’t breastfeed and took medicine. I didn't know this was possible, but I agreed straight away."

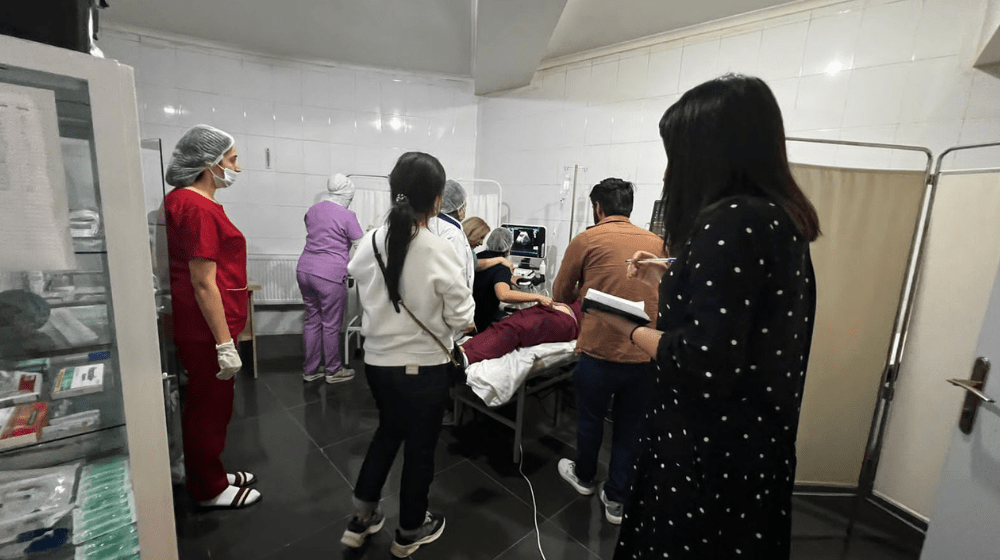

In 2022, UNFPA, in partnership with the Ministry of Health, the State Agency for Compulsory Medical Insurance and the Administration of Regional Medical Divisions (TABIB), started the "Safe motherhood in the southern region of Azerbaijan" project aimed at promoting safe childbirth, reducing preventable maternal and child mortality and improving women's and girls' reproductive health by training medical staff at local health care institutions.

HIV treatment is free in Azerbaijan and UNFPA's national partner, the Republican AIDS Center, is the only institution that deals with HIV detection, prevention and treatment. Its services helped Ms. Hasanova during her pregnancy - and it also helped a member of her medical care team.

Gulsum Mammadova was one of the nurses preparing Ms. Hasanova for her delivery. While taking a blood sample, Ms. Mammadova accidentally inserted the needle into her own finger. “The world stopped for a moment,” she said. “I was very scared. My children and relatives appeared before my eyes. The first thing that came to my mind was that I have been infected with HIV, there is no cure for it, and I will die soon."

But Ms. Mammadova was able to overcome her initial panic by remembering the training she received through the UNFPA programme. She had learned that even after contact with HIV, it is possible to minimize the risk of infection by using post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) within the first 72 hours of exposure.

So Ms. Mammadova immediately informed her colleagues at the perinatal clinic about the incident. The management contacted the Republican AIDS Center and sent her for a consultation. “At the centre, I was examined and given medicine on the same day,” she said. After taking the PEP medicine for 28 days, Ms. Mammadova returned for follow-up tests that were all negative for HIV. It has now been more than six months since she punctured her finger and Ms. Mammadova is still HIV-free: “I will go on with my life in peace."

Meanwhile, Ms. Hasanova’s life is also at peace after giving birth. Her child has not shown any signs of HIV infection.

“If my son continues to test negative after 18 months, he will be considered free of HIV,” said Ms. Hasanova.

*All names in this story have been changed to protect anonymity.